There’s an elegant spider’s web woven between the bars of an open window on the top landing of Helsinki’s Hotel Katajanokka. Some might call it shoddy housekeeping, but I’m thrilled by the unintentional symbolism, given that one of the most common prison tattoos, representing entrapment in the system, is that of a spider’s web.

Before it was turned into a four-star hotel, the Hotel Katajanokka was a prison. The oldest parts of this stern-looking red brick building date back to 1837. “The food there smelled like piss and shit,” writes former prisoner Marko Lönnqvist in his memoir Elämäni Gangsterina (My Life as a Gangster). That’s because, until the prison closed in 2002, there were no toilets, and prisoners had to relieve themselves in buckets in their cells, demonstrating the sort of sisu, or grit, which is considered part of the national character.

Fortunately, things on the bathroom front have changed, I reflect, as I head to the spacious shower in my room. I follow it up with a session in the basement sauna, and then the sleep of the jetlagged or dead, because not a sound makes it through these metre-thick prison walls.

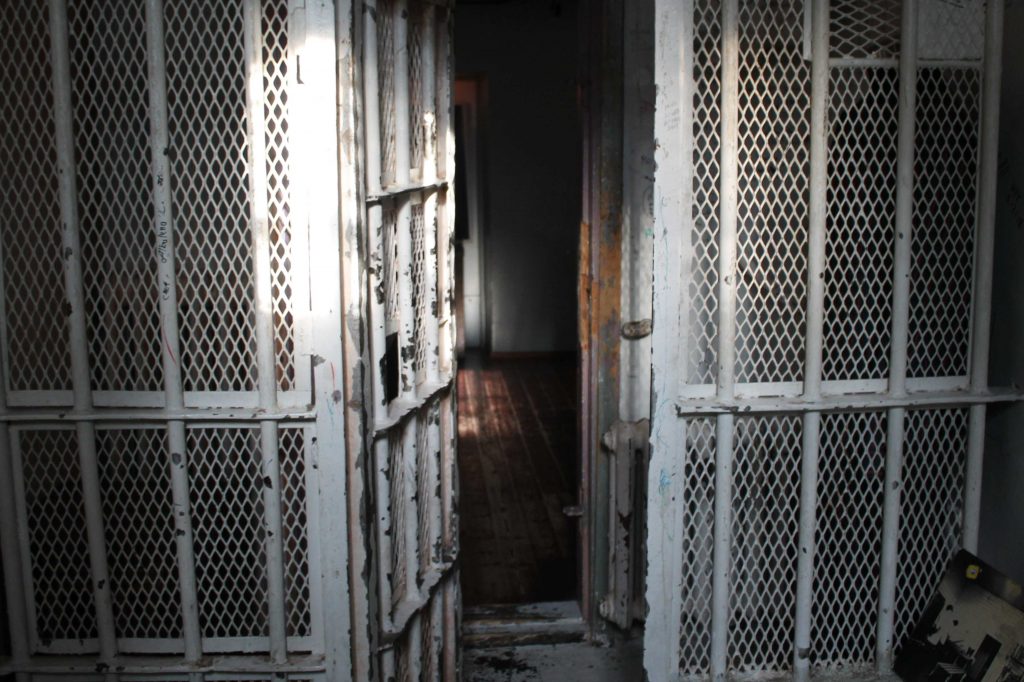

Extensive restoration work over a period of five years was undertaken to turn the Hotel Katajanokka into today’s haven of comfort. The open central corridor with utilitarian metal steps, and the high perimeter wall surrounding the grounds, are protected by the National Board of Antiquities, while a couple of original cells, complete with graffiti, remain preserved on the lower floor.

But the hard edges have been softened with lush carpet and natural light; the rooms, occupying the space of two to three cells each, have feather-soft beds; and the yards in which prisoners sought exercise or escape now boast kitchen gardens and park benches. As such, the Hotel Katajanokka represents the perfect launching pad for a few days spent exploring Helsinki’s grittier side.

Tim Bird/Governing Body of Suomenlinna

Flying free. Denise Cullen

I say that because although Finland has been rated as the happiest nation of earth, according to the UN’s 2018 World Happiness Report, dark clouds still hang over this land of breathtaking natural beauty, 3.3 million saunas and 187,888 lakes. For example, one third of Finns are estimated to be affected by alcoholism. The nation ranks a surprising eighth in the world in terms of gun ownership per capita. Then there are the long, harsh Nordic winters, and the mood disorders which follow.

I spend an afternoon on Suomenlinna Island, a short ferry ride from downtown Helsinki. Construction on this historical sea fortress commenced as far back as 1748 and , during the Finnish Civil War in 1918, a prison camp was set at the fortress. In 1991, Suomenlinna was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in recognition of its military architecture. Today, visitors are free to explore the monuments and roam the windswept cliffs. While following a cobblestone street, I rounded a corner and came face to face with one of Finland’s famous open prisons. A picket fence is all that separates the prison grounds from the rest of the island. As I take photographs, a prisoner lights a cigarette and waves to me from the deck of his cabin.

“Helsinki has been occupied, burned and bombed,” says Finnish journalist and crime fiction author Jarkko Sipilä. “People in the city have been swindled, killed and frozen to death.” Since 2016, Sipilä has been running free walking tours of his native Helsinki, using many of the landmarks which appear in his Helsinki Homicide series, to tell the human stories behind the city’s multi-layered history. “The crimes range from murder to scams to espionage and they date from the early 20th century to very recent events,” Sipilä says. Sipilä’s walking season runs from May to October. “I’ve done a few in December, but you really need an ice fishing suit for those, it’s not very fun,” he quips.

Focusing on the shopping district of Aleksanterinkatu in downtown Helsinki, he usually starts at Senate Square, where a bomb exploded in 1905 as part of a failed assassination attempt upon a member of the Russian aristocracy. The bomb, it emerged, had been built by a student activist in the University of Helsinki’s chemistry department, in protest at the “Russification” of formerly autonomous Finland, Sipilä says. More than a century later, the same university would become the site of a foiled mass shooting and poison gas attack which was intended to kill 50 people. When police, acting on a tip-off, arrested the two suspects in 2014, they seized a crossbow, handcuffs, cartridges, tactical vests, a gas mask, gunpowder, bullets and laboratory equipment.

The Helsinki Murder Walk run by Green Cap Tours explores a different part of the city, the bohemian district of Punavuori, over two hours and more than a dozen stops, says Mikael Penttilä. Here lies Tom Sjöberg’s notorious sex shop, and the site where, in 1942, 51 people, many of them children waiting to see The Three Musketeers at the theatre, were killed in a bombing raid. The address where a tax law professor was murdered in 2006 in a robbery gone wrong is another stop on the tour. Among the more bizarre aspects of the case was that although the victim’s apartment was filled with expensive art, the perpetrators got away with only cigarettes, liquor and a small amount of cash.

The Helsinki Horror Walk, led by Happy Guide Helsinki, provides a more supernatural spin on the city, with ghost stories and urban legends set against a backdrop of architectural show-stoppers such as Uspenski Cathedral. Organisers claim the “unexplained happenings” in almost every historic building in the city centre may be attributed to the fact that ancient cemeteries lie under the foundations.

The Helsinki City Museum, too, offers a couple of walks which give glimpses of ghastly phenomenon such as the Alexander Theatre ghost, and the half dozen restless spirits at the National Theatre. Another well-known apparition is that of Russian Colonel Aleksi of Vironkatu. Legend has it that in the early 1900s, deranged by grief after finding his wife with another man, he took his life and continues to seek happiness in his former home. Some claim to have seen him in the elevator of the building which now stands on the site, holding his head under his arm, thus earning himself the nickname of the Headless Colonel.

© Denise Cullen